Chapter 15: Concerning Things for Which Men, And Especially Princes, Are Praised or Blamed

It remains now to see what ought to be the rules of conduct for a prince towards subject and friends. And as I know that many have written on this point, I expect I shall be considered presumptuous in mentioning it again, especially as in discussing it I shall depart from the methods of other people. But, it being my intention to write a thing which shall be useful to him who apprehends it, it appears to me more appropriate to follow up the real truth of the matter than the imagination of it; for many have pictured republics and principalities which in fact have never been known or seen, because how one lives is so far distant from how one ought to live, that he who neglects what is done for what ought to be done, sooner effects his ruin than his preservation; for a man who wishes to act entirely up to his professions of virtue soon meets with what destroys him among so much that is evil.

Hence it is necessary for a prince wishing to hold his own to know how to do wrong, and to make use of it or not according to necessity. Therefore, putting on one side imaginary things concerning a prince, and discussing those which are real, I say that all men when they are spoken of, and chiefly princes for being more highly placed, are remarkable for some of those qualities which bring them either blame or praise; and thus it is that one is reputed liberal, another miserly, using a Tuscan term (because an avaricious person in our language is still he who desires to possess by robbery, whilst we call one miserly who deprives himself too much of the use of his own); one is reputed generous, one rapacious; one cruel, one compassionate; one faithless, another faithful; one effeminate and cowardly, another bold and brave; one affable, another haughty; one lascivious, another chaste; one sincere, another cunning; one hard, another easy; one grave, another frivolous; one religious, another unbelieving, and the like. And I know that everyone will confess that it would be most praiseworthy in a prince to exhibit all the above qualities that are considered good; but because they can neither be entirely possessed nor observed, for human conditions do not permit it, it is necessary for him to be sufficiently prudent that he may know how to avoid the reproach of those vices which would lose him his state; and also to keep himself, if it be possible, from those which would not lose him it; but this not being possible, he may with less hesitation abandon himself to them. And again, he need not make himself uneasy at incurring a reproach for those vices without which the state can only be saved with difficulty, for if everything is considered carefully, it will be found that something which looks like virtue, if followed, would be his ruin; whilst something else, which looks like vice, yet followed brings him security and prosperity.

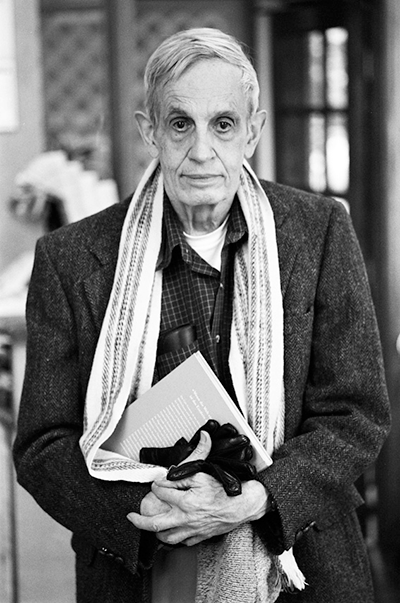

A modern Machiavellian? John Forbes Nash Jr. (1928 - 2015) mathematician, 1994 Nobel laureate in Economics, and a practitioner of Game Theory. His life was the subject of the movie A Beautiful Mind. Attribution: By Peter Badge / Typos1 (OTRS submission by way of Jimmy Wales) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Machiavelli’s Political Realism

Machiavelli, in this chapter, announces his intention to challenge the idea that conventional morality applies to a prince, i.e. an autocratic ruler, as opposed to a republic. In the next 3 chapters, he will contend that a prince, when acting as the head of state, simply cannot afford to abide by the same moral code that we consider commendable in a private citizen. In particular, we commend an ordinary person if he is generous, merciful, and faithful (true to his word). However, Niccolò believes that for a prince (in his public capacity) practicing these conventional virtues is so dangerous as to make it difficult for a prince to preserve his state.

Today we identify this notion as one of the tenants of the school of political science known as political realism. Hans Morgenthau (1904 - 1980) the father of modern political realism, in his Politics among Nations (p10) puts it as follows. “Realism maintains the universal moral principles cannot be applied to the actions of nation states in their abstract universal formulation … The individual may say for himself ‘Let justice be done even if the world perish’ but the state has no right to say so in the name of those who are in its care.”

In the next three chapters, he will cite specific reasons. In this chapter he gives an interesting general reason. He contends that a prince cannot rely on other princes to observe the virtues (mercy, generosity, and fidelity). It would have been obvious to his audience not only that, in Renaissance Italy princes did not observe these virtues, but that every prince had aggressive competitors. Therefore, Machiavelli says, a prince that observes these virtues when his opponents do not “soon meets with what destroys him among so much that is evil.”

It is interesting that Machiavelli’s point here is completely compatible with a modern analysis. For example, we can make the same point in terms of strategy. Suppose that we think of each prince as having a choice of two strategies: virtue and vice. Obviously, it would be best for all concerned if every prince chose virtue. But there is no path of logical reasoning that could lead competitive powers to cooperate by simultaneously choosing the strategy of virtue.

Each prince can reason as follows. “If my opponent chooses vice, not only will he enjoy a dramatic competitive advantage (i.e., he will profit more than I do), but he will profit at my expense. Thus he will grow stronger while I grow weaker. I cannot allow this to happen, therefore, I too must choose vice.” Strategists who study a branch of mathematics called Game Theory, refer to this dynamic as “The Prisoner’s Dilemma. I do not contend that Machiavelli anticipated game theory, merely that his ideas have weight because they have not been overthrown but rather confirmed by modern analysis.

Or as Hans Morgenthau says (in Politics among Nations p36): “If the desire for power cannot be abolished everywhere in the world, those who might be cured would simply fall victims to the power of others.”