Chapter I - How Many Kinds of Principalities There Are, and By What Means They Are Acquired

All states, all powers, that have held and hold rule over men have been and are either republics or principalities.

Principalities are either hereditary, in which the family has been long established; or they are new.

The new are either entirely new, as was Milan to Francesco Sforza, or they are, as it were, members annexed to the hereditary state of the prince who has acquired them, as was the kingdom of Naples to that of the King of Spain.

Such dominions thus acquired are either accustomed to live under a prince, or to live in freedom; and are acquired either by the arms of the prince himself, or of others, or else by fortune or by ability.

Roman Republic with a monarchical form of government,

known as the Principate (27 BCE – 284 AD), in which he

preserved the illusion of a republican form of government. By

the time that Machaivalli dedicated The Prince to Lorenzo Di Piero

De’ Medici, the government of Florence had also become a

principate (or principality in our translation).

Strategy

In this short chapter, Machiavelli states the scope of the book and sketches several scenarios by which a prince may acquire power. He will add layers of elaboration in the first (what I will call the Strategy) part of the book. As you will see, Machiavelli constructs his exposition in layers much like an artist would paint a picture. He first blocks out the general form, then in later chapters adds layers of form and color to particular portions of his canvas. In the comments, I will remark on how the parts of his composition fit together to form a coherent and artistic whole.

At the outset, you will want to know two things about Machiavelli that are at variance with what we might think of as Machiavellian.

First, we might think of a Machiavellian as someone who glorifies dictatorship. But, Machiavelli actually thought that a republican form of government was superior to that of a principality. Machiavelli is best remembered for his advice to a Prince, simply because, as he says here, The Prince, his best known book, deals only with principalities.

In his much longer book, The Discourses, Machiavelli makes it clear that he greatly prefers republics to principalities (see for example The Discourses, Book 2 Chapter 2. He thinks principalities have their place in the early days of a state, but he considers republics a more stable, stronger, and humane form of government. He also holds up the Roman Republic (509 BC - 27 BCE) as a model. The Republic perished between 45 BCE when Julius Caesar overthrew the republic and 27 BCE when Caesar Augustus ensured that it would not return by establishing a lasting but autocratic form of government that historians call the Principate. It is this sort of government (i.e. a principality) that Machiavelli is writing about here.

Given that Machiavelli prefers republics to principalities, we see that The Prince has a subtext. That is, when he gives advice to a prince, he is not only saying what a prince should do, if he wishes to be successful, he is also saying what a prince must do if he wishes to survive. To put the matter in his own words:

“How one lives is so far distant from how one ought to live, that he who neglects what is done for what ought to be done, sooner effects his ruin than his preservation; for a man who wishes to act entirely up to his professions of virtue soon meets with what destroys him among so much that is evil.”

The Prince, “Chapter 15: Concerning Things for Which Men, And Especially Princes, Are Praised or Blamed”

In the course of The Prince, Machiavelli will contend that a prince must behave with calculated ruthlessness. Saying that an autocratic ruler is obliged to be ruthless is not at all the same thing as saying the he ought to be ruthless, and is very different from saying that everyone should be ruthless. Nonetheless, even saying this much, is a contentious idea, because it implies that all princes and by extension all those who hold autocratic power must behave in a way that should make us decidedly uncomfortable and suspicious of them.

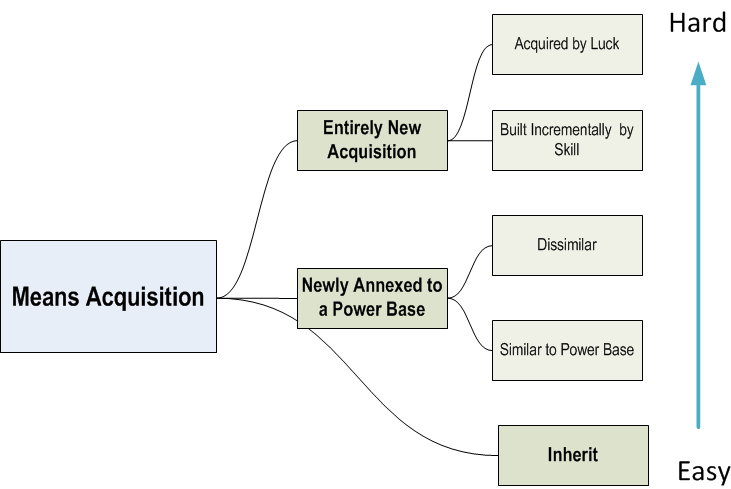

A schematic diagram of the usual means by which princes come to power and Machiavelli’s rating of the degree of difficulty of holding power in each case.

There is a second point where the real Machiavelli fails to be precisely Machiavellian. We might think of Machiavelli as a character like Shakespeare’s Richard III, someone who is obsessively concerned with plotting to grab power. However, The Prince, is not concerned with how to grab territory or power, but how to secure and maintain newly acquired power in the face of inevitable internal and external challenges.

In the first 11 chapters, Machiavelli will be concerned primarily with the strategy that a prince who has recently acquired power, can use to reach a political settlement that allows him to consolidate and hold his newly acquired state. Machiavelli considers how the prince gains power only because, the circumstances influence the kind and magnitude of the problems that the prince will have in keeping power.

In the first seven of the strategy chapters, Machiavelli presents an idealized picture of the usual means by which princes come to power and he ranks them according to the degree of difficulty of holding power in each case. The prince who inherits power has the easiest task in keeping it. Next, a prince who enhances his power by annexing new territory has additional difficulties in holding it securely. A prince who attempts to found a new state, without even starting from a hereditary powerbase has formidable difficulties in integrating, organizing, and controlling the new state. However, Machiavelli contends that those who found a state incrementally over time and with their own resources, have a better chance of hanging on to their state than do people (like Lorenzo Di Piero De’ Medici) who are assisted by good luck or the resources of a benefactor.

Machiavelli will (in what I think is a surprisingly modern way) stress the importance of organization. He will contend that the difficulty of securing power increases with the extent of the social and political change required, and decreases to the extent that the prince has sufficient time to acquire the necessary resources, organization and skill.

In the last 4 of the strategy chapters Machiavelli considers four means of acquiring power that do not fit exactly into the general pattern.

The remaining 15 chapters concern the policy that the prince must follow to retain power.