Chapter 4: Why the Kingdom of Darius, Conquered by Alexander, Did Not Rebel Against the Successors of Alexander at His Death

Considering the difficulties which men have had to hold to a newly acquired state, some might wonder how, seeing that Alexander the Great became the master of Asia in a few years, and died whilst it was scarcely settled (whence it might appear reasonable that the whole empire would have rebelled), nevertheless his successors maintained themselves, and had to meet no other difficulty than that which arose among themselves from their own ambitions.

I answer that the principalities of which one has record are found to be governed in two different ways; either by a prince, with a body of servants, who assist him to govern the kingdom as ministers by his favor and permission; or by a prince and barons, who hold that dignity by antiquity of blood and not by the grace of the prince. Such barons have states and their own subjects, who recognize them as lords and hold them in natural affection. Those states that are governed by a prince and his servants hold their prince in more consideration, because in all the country there is no one who is recognized as superior to him, and if they yield obedience to another they do it as to a minister and official, and they do not bear him any particular affection.

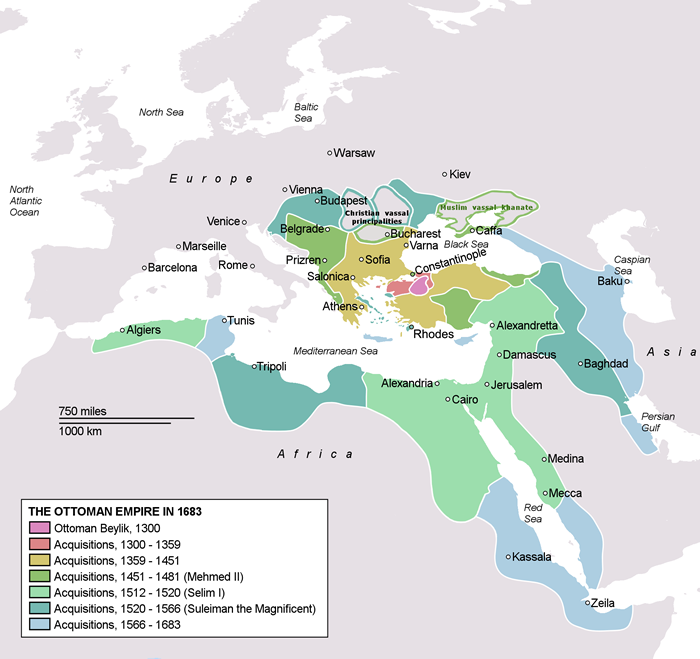

The examples of these two governments in our time are the Turk and the King of France. The entire monarchy of the Turk is governed by one lord, the others are his servants; and, dividing his kingdom into sanjaks [administrative districts], he sends there different administrators, and shifts and changes them as he chooses. But the King of France is placed in the midst of an ancient body of lords, acknowledged by their own subjects, and beloved by them; they have their own prerogatives, nor can the king take these away except at his peril. Therefore, he who considers both of these states will recognize great difficulties in seizing the state of the Turk, but, once it is conquered, great ease in holding it. The causes of the difficulties in seizing the kingdom of the Turk are that the usurper cannot be called in by the princes of the kingdom, nor can he hope to be assisted in his designs by the revolt of those whom the lord has around him. This arises from the reasons given above; for his ministers, being all slaves and bondmen, can only be corrupted with great difficulty, and one can expect little advantage from them when they have been corrupted, as they cannot carry the people with them, for the reasons assigned. Hence, he who attacks the Turk must bear in mind that he will find him united, and he will have to rely more on his own strength than on the revolt of others; but, if once the Turk has been conquered, and routed in the field in such a way that he cannot replace his armies, there is nothing to fear but the family of this prince, and, this being exterminated, there remains no one to fear, the others having no credit with the people; and as the conqueror did not rely on them before his victory, so he ought not to fear them after it.

The contrary happens in kingdoms governed like that of France, because one can easily enter there by gaining over some baron of the kingdom, for one always finds malcontents and such as desire a change. Such men, for the reasons given, can open the way into the state and render the victory easy; but if you wish to hold it afterwards, you meet with infinite difficulties, both from those who have assisted you and from those you have crushed. Nor is it enough for you to have exterminated the family of the prince, because the lords that remain make themselves the heads of fresh movements against you, and as you are unable either to satisfy or exterminate them, that state is lost whenever time brings the opportunity.

Now if you will consider what was the nature of the government of Darius, you will find it similar to the kingdom of the Turk, and therefore it was only necessary for Alexander, first to overthrow him in the field, and then to take the country from him. After which victory, Darius being killed, the state remained secure to Alexander, for the above reasons. And if his successors had been united they would have enjoyed it securely and at their ease, for there were no tumults raised in the kingdom except those they provoked themselves.

But it is impossible to hold with such tranquility states constituted like that of France. Hence arose those frequent rebellions against the Romans in Spain, France, and Greece, owing to the many principalities there were in these states, of which, as long as the memory of them endured, the Romans always held an insecure possession; but with the power and long continuance of the empire the memory of them passed away, and the Romans then became secure possessors. And when fighting afterwards amongst themselves, each one was able to attach to himself his own parts of the country, according to the authority he had assumed there; and the family of the former lord being exterminated, none other than the Romans were acknowledged.

When these things are remembered no one will marvel at the ease with which Alexander held the Empire of Asia, or at the difficulties which others have had to keep an acquisition, such as Pyrrhus and many more; this is not occasioned by the little or abundance of ability in the conqueror, but by the want of uniformity in the subject state.

Centralized Control

Between 334 and 330 BCE, Alexander the Great (356 – 323 BCE) king of the small Greek state of Macedon conquered the gigantic Achaemenid Persia Empire of Darius III (380 – 330 BCE). Machiavelli has in Chapter 3 just finished telling us how difficult it is to hold on to conquered territory. Alexander’s difficulties should have been worse than most given the disparity in the size of his small power base in Macedon and the Persian empire of Darius. To make matters still more difficult, Alexander died soon after the conquest. Nevertheless, the empire did not devolve into anarchy. Instead, it was divided among his top generals and the resulting states survived, free from internal revolt. Squabbles among the successors changed boundaries, but the block of successor kingdoms remained stable for 300 years, the Hellenistic Period, which decisively imprinted Greek culture on the east. The block of successor states remained free from outside invasion until the Roman conquest of the Greek east. The last and most stable Hellenistic state Egypt (founded by Alexander’s general Ptolemy) was not conquered until the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE when Caesar Augustus defeated Mark Anthony and the last Ptolemaic ruler, Cleopatra.

In this chapter, Machiavelli is still concerned not with conquest but with the political settlement whereby conquers can pacify and hold new territory. He focuses here on the special issue of the state’s organization and the role of the family.

Within a feudal state power was decentralized and distributed. A feudal lord, e.g. a king, had a contractual relationship with his vassals. The lord was the dominant partner, and in that sense ruled his vassals (e.g. dukes), but not necessarily the vassals’ vassals (counts or knights), or their subjects. The feudal state was made up of many local power centers that were dominated by families. The executive power of the ruler of a feudal state was always opposed by an oligarchy of the most prominent noble families. Even as the feudal states became more centralized monarchies, factionalism within the old families of the noble oligarchy remained the most prominent internal threat to a ruler’s authority.

By contrast, the governmental system of the Ottoman Turks was based on central, as opposed to distributed control. The sultan’s authority was not contractual, but absolute. Local officials held no autonomous power, but only delegated authority. The sultan’s power thus passed directly to the lowest subject. In this system, there was no oligarchy of noble families. However, Sultans were aware of the danger posed by family rivalries. They commonly followed a practice of strangling their own brothers immediately after the birth of the sultan’s first son.